White papers

WHEN GROWTH STALLS: ANTICIPATING A GROWTH INVESTOR'S GREATEST CHALLENGE

ARCHIVED - 24-Jun-2018

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Growth stocks naturally tend to command premium valuations to reflect their attractive earnings profile

- While growth lasts, all is well. Any unexpected halt, however, can be painful as investor expectations are re-set

- Using Tesco as an example, this White Paper attempts to demonstrate how long-term investors can spot a future stall in order to sell out in time

INTRODUCTION

On 28 September 2017, Sasha Wass QC, a lawyer for the United Kingdom’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO), stood up to address the jury at Southwark Crown court in London:

“This case concerns what is often referred to as white collar crime and it concerns fraud and false accounting...

…On 22 September 2014…Tesco Plc made a public announcement to the stock market and the announcement said that Tesco’s had previously overstated its expected profits by approximately £250million.

…[The defendants] encouraged the manipulation of profits and indeed pressurised others working under their control to misconduct themselves.”

Tesco’s fall from grace could hardly have been less elegant. For much of its history, the multinational supermarket chain was a darling of the stock market and a mainstay of most UK portfolios. It became known as a “ten percenter”, referring to its remarkably consistent ability to deliver 10% earnings growth per annum with a share price that followed. CEO Sir Terry Leahy, who stepped down in 2011, was even knighted for his achievements.1

Half a decade later, the shares have lost 60% of their value, profits have collapsed and three senior executives were put on trial by the SFO2. The question for many is, how did they get there?

In our view, Tesco is an excellent example of a growth investor’s greatest challenge: what happens when growth stalls and, more importantly, how best to anticipate it.

“If it seems too good to be true, it usually is.”

By their nature growth stocks tend to command premium valuations to reflect their compelling earnings profile. This is well and good as long as the growth lasts, but should it stop unexpectedly, or stall, the result is a painful combination of a falling valuation multiple on falling earnings and/or cash flow. This is exactly what happened to Tesco.

A stall’s genesis can often be traced back to many years before it actually happened, resulting in a trail of red flags that could forewarn an investor

In this White Paper, we intend to demonstrate how an investor using the appropriate framework can potentially avoid stock market calamities of this kind. It is our contention that stalls rarely come out of the blue. Far from it. In many cases the genesis of the stall can be traced back to many years before it actually happened, resulting in a trail of red flags that could alert the investor of the impending stall.

We have chosen to focus on Tesco, in part because the recent court case makes it topical, but also because we believe the lessons from this case study can be applied to countless others. (It also helps that this author was a sell-side analyst covering the company during this period.)

TESCO CASE STUDY

The Good Years

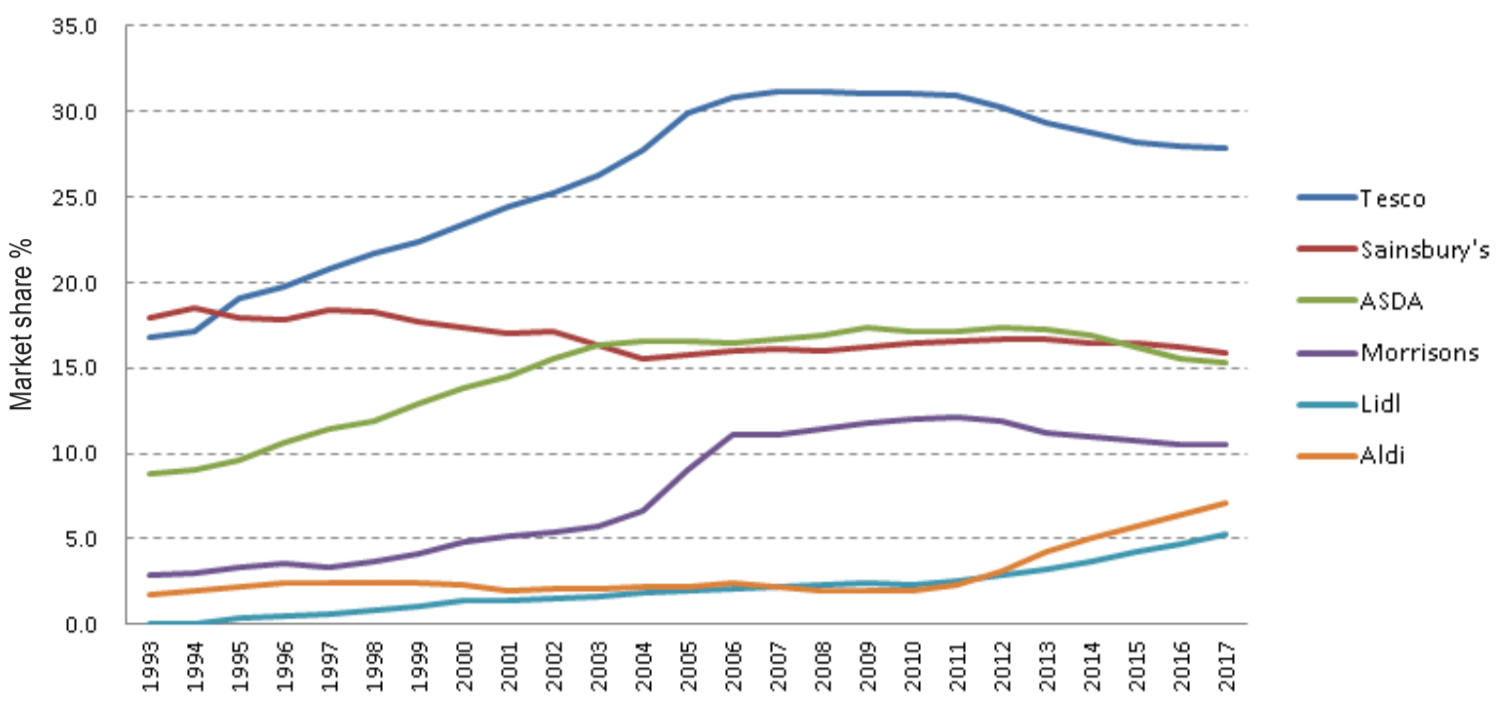

The numbers spoke for themselves. Tesco’s rise was vertiginous. As shown in figure 1, from the early nineties to the mid-noughties, its UK market share grew from 16% to 32%, overtaking local competitor Sainsbury’s to the number one spot along the way.

A combination of low prices, controlled expansion and flawless execution led sales to quadruple and profits to rise fivefold over that period. Tesco was an undisputed success story.

Source: Kantar

Source: Kantar

By the early 2000s, it became apparent that within a few years the company was going to hit a market share ceiling in its home market. The question for management was, what next?

The Warning Signs

Aggressive and Capital - Consumptive Expansion into New Markets

Even while Tesco was taking market share back home, management attention shifted to an aggressive international expansion effort, requiring substantial capital. The company entered its first international market as far back as 1995 with the acquisition of S-Market in Hungary, which it followed up with the Czech Republic (1996), Slovakia (1996), Poland (1997; 2006), Thailand (1998), South Korea (1999), Malaysia (2002), Turkey (2003), Japan (2003), China (2004), the US (2007), and finally India (2008).

Over time, Tesco’s capital allocation became increasingly aggressive with the most egregious example being the company’s entry into the mature US market in 2007. Following two years of highly secretive testing, Tesco opened its first Fresh and Easy store to great fanfare. Over the course of the following five years, the company sank in an excess of $5bn in order to fit out and run 200 small leasehold stores3. Fresh and Easy never turned a profit and at peak generated just $1bn of revenue. In 2013, Tesco paid a private equity group to take the albatross off its hands.

Resorting to Increasingly Complex Financing

Funding such largesse began to take a financial toll and by 2008 leverage had risen to over 4x EBITDA. Rather than scale back, Tesco looked to off-balance sheet financing in the form of sale and leasebacks in order to continue its binge. Between 2004 and 2011, Tesco raised £5.5bn by selling large chunks of its UK property portfolio and entering into long-term lease agreements (most controversially with its own pension fund). By 2011, Tesco’s off- balance sheet liabilities had become as large as its on-balance sheet debt. And yet, the market continued to blindly applaud its double-digit earnings growth.

Core Business Problems

Whether a function of the cash-flow constraints resulting from the company’s international flag-planting strategy or perhaps simply a question of “taking their eye off the ball,” Tesco’s UK business began losing ground around this time. Over the course of a number of years the company’s price positioning gradually deteriorated and consumers noticed. Traffic in the stores began declining, albeit off a high base, and for the first time in over a decade, Tesco began losing share. To compensate for lost traffic, Tesco chose to protect its margin by raising prices. Over time competitors followed the price setter, Tesco, and the UK became one of the most expensive countries for food in Europe (the Daily Mail called it “rip-off Britain”4), which is one of the principal reasons why discounters Aldi and Lidl finally got a foothold in the country beginning in 20105.

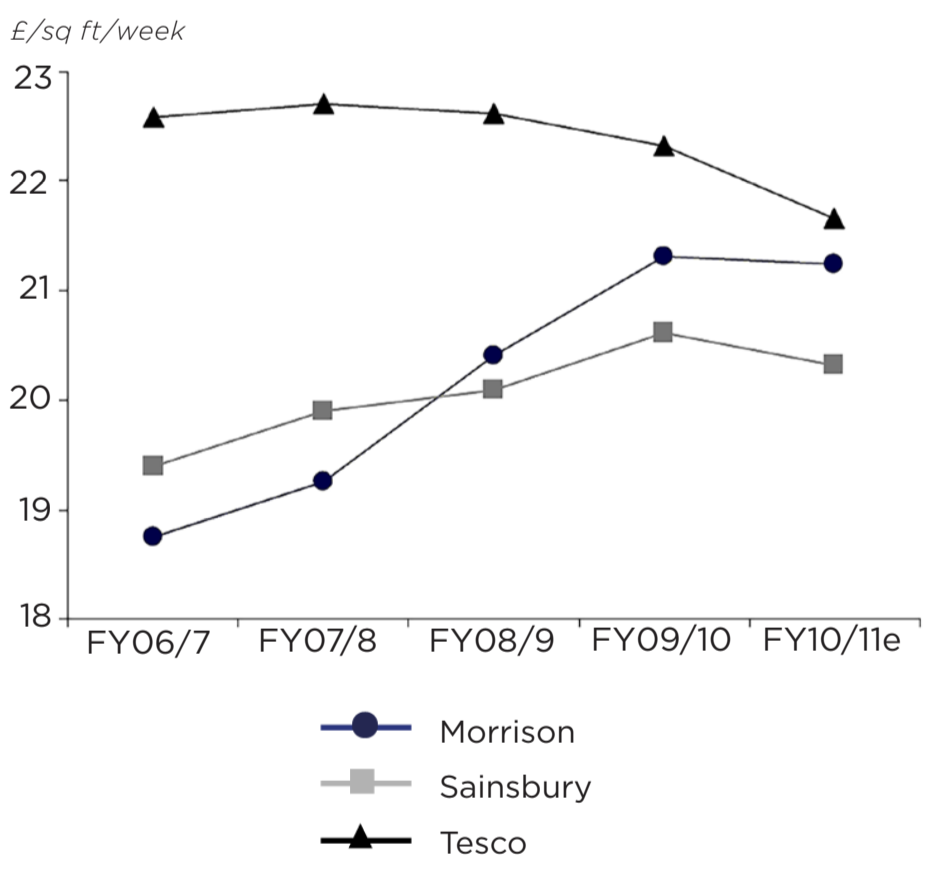

But the cow wasn’t just being milked in the UK – in virtually all of its international markets Tesco’s sales densities were declining, and yet profits were rising. Something was bound to give at some point, but Tesco was doing its utmost to push out that day of reckoning.

Increasingly Aggressive Accounting Policies

Arguably the strongest warning signal that all was not what it seemed at the surface came from the rapid deterioration in the quality of Tesco’s accounts, which were increasingly beginning massaged in order to maintain the appearance of steady profit growth.

Source: Johnston and Wittet. “Tesco – Coming Up for Air”. Citigroup Global Markets, Citigroup Investment Research & Analysis. 2 March 2011.

Source: Johnston and Wittet. “Tesco – Coming Up for Air”. Citigroup Global Markets, Citigroup Investment Research & Analysis. 2 March 2011.

The creative accounting started with adjustments to the statutory accounts. Until 2005 Tesco made virtually no adjustments, presenting simply the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) accounts adjusted for exceptional items like disposals or integration costs. Beginning in 2006, the company added pension adjustments. By 2010, Tesco was adjusting for a whole litany of things, from customer loyalty programs to the treatment of leases6. Needless to say, the sum of the adjustments inflated their definition of earnings and grew with time.

Beyond the company’s adjusted figures, Tesco’s audited figures should also have raised some eyebrows. When compared to peers, Tesco was regularly using more aggressive assumptions, whether depreciation (assuming longer useful lives), returns on pension assets (assuming higher returns), or the life expectancy of its employees (assuming they would die two years younger than peers).7Tesco would capitalise not just the investment in building a new supermarket (which is normal), but a significant amount of the interest associated with the investment. None of its peers, even Walmart (which built significantly more stores than Tesco), did this.

When the accounting scandal was uncovered in 2014, it came to light that in the first half of that year the company had been over-booking supplier rebates and overstating profits. The inquiry widened, and it was subsequently revealed that the company had been engaging in aggressive and fraudulent accounting practices across the board, such as capitalising shop floor staff as inventory.

Extensive Change at the Top

In 2011, after 14 years at the helm and months before the first profit warning, CEO Sir Terry Leahy retired. In less than a year, a significant number of fellow executives followed suit by leaving Tesco, including: Chairman, David Reid; Board Director, Andrew Higginson; Head of Asia, David Potts; Head of UK, Richard Brasher; Head of Online, Laura Wade-Gery; and Head of US, Tim Mason.

Within a short time period, new CEO Philip Clarke saw his executive committee of eight evaporate until only he was left. Something wasn’t right, and it was clear that the old guard knew it.

Culture – The Dog That Didn’t Bark

A company’s culture is the common ingredient linking the red flags of a stall

The common ingredient that unites all of these red flags, and the dimension in our opinion that lies at the core of Tesco’s demise, was its culture. Tesco had the reputation for being a tough and uncompromising organisation (part of its success could no doubt be attributed to this, for example in relation to supplier negotiations or securing its expansion pipeline8), a trait that could be traced back to its founder Jack “Slasher” Cohen9. He came from a hardscrabble part of London and was known for having a tireless work ethic: he would reportedly give favoured executives a tie-pin with the inscription, “YCDBSOYA” (You Can’t Do Business Sitting On Your *rse).

Under Sir Terry Leahy (CEO; 1997-2011) the culture evolved into a culture of fear which worsened under Philip Clarke (CEO; 2011-2014). In a piece written in The Independent soon after the company’s demise, a number of former staff members attested to a regimented atmosphere where financial and performance targets were king, and where those who failed to meet them would be publicly humiliated10. At the trial, Amit Soni, the whistle- blower who revealed the accounting fraud, testified that there was “pressure from within” to close the “performance gap,” with one senior executive telling him to “go back and meet the plan and hit the numbers”11.

Suppliers could also feel the pressure. There are accounts of buyers being ordered to “find me £30m”12and of suppliers being paid late or, in some cases, not at all (with the threat of being cut from the supplier list permanently if they complained).

The truth is Tesco had reached maturity and refused to admit it, doing everything it could to keep the music playing. Everything in its culture meant it had to keep growing in order to deliver on its “ten percenter” reputation, regardless of the risks and costs involved.

In contrast to Tesco, rather than chasing risky attempts at international expansion – one Belgian business slowed its store opening profile and began generating substantial cash flows

It didn’t have to be this way. At around the same time that Tesco was seeing its market share plateau in the UK, a small family-run business in Belgium called Colruyt was experiencing a similar phenomenon: it had dominated its home market for decades and was hitting a market share ceiling of 30%. How it responded stands out as much for its rarity as for its common sense: it simply slowed its growth. Rather than chase after increasingly risky attempts at international expansion – in an industry scattered with examples of failed overseas strategies – it slowed its store opening profile and began generating substantial cash flows. Ten years later, Colruyt’s shares are valued 50% higher while Tesco’s are 60% lower. The difference has nothing to do with their individual circumstances and everything to do with how they chose to respond to the same dilemma: what to do when a business matures. (This incidentally is also part of the reason Comgest likes family-owned businesses: people tend to be more careful when it’s their own money at stake.)

IDENTIFYING A GROWTH STALL: RED FLAGS

While in hindsight the warning signs of a stall such as Tesco’s seem obvious, at the time they are anything but. The truth is stalls are remarkably difficult to see coming, for two principal reasons.

The first has to do with the peculiarity of a growth company’s mindset, which means it is wired to look for growth, sometimes regardless of the cost. From the structure of management remuneration packages to the capacity to attract and retain talent, the incentives for a growth company to maintain growth are immense and sometimes come at the expense of financial discipline. Hence, indicators such as sales or earnings growth tend to reveal little: they can be “bought,” at least in the short term. Be it through M&A, greater capital expenditure, unsustainable price increases, short-term cost-cutting, or accounting trickery, it is often possible to give the illusion of growth, at least for a while.

The second reason has to do with the investor’s mind-set and a bias that behavioural economists call the endowment effect. Researchers have shown in a variety of contexts that owning something – your “endowment” – makes it more valuable to the owner than it was before; perhaps the most egregious example being that you’ll demand a higher price than you paid to sell a lottery ticket you own, despite the odds of winning having remained constant. It’s not just a lottery ticket, it’s your lottery ticket, and the fact of ownership confers higher (perceived) value.

A longer-than-average holding period means a greater risk of emotional attachment to owned companies, which can cloud judgment

For bottom-up, buy-and-hold portfolio managers like Comgest, the “objects of ownership” are the stocks we hold in our portfolios. We’ve conducted in-depth fundamental research, met with management, competitors, suppliers, customers and industry experts alike. In all, the process can take years and once the stock is bought it can be held for decades. Compared to a typical asset manager with stock holding periods of a year or less, our substantially longer-average holding period means we run a much greater risk of creating an emotional attachment to the companies we own, which in turn can cloud our judgment.

In order to overcome these hurdles we need to work within a framework which helps to ensure that we stay alert to the early warning signs of a growth stall, recording the flags as they present themselves. Over time the accumulation, or not, of these flags will enable us to assess objectively whether a growth stall has set in and help us to shed our previous views of a company we liked and admired.

Awareness of potential red flags could help an investor to reassess their views and exit a holding at the right timeTo that end, and to the extent that our experience allows us to, we humbly offer up the following (non-exhaustive) list of potential red flags:

- Deteriorating Fundamentals: Most stalls start with a deterioration of the fundamental indicators of success, be it market share, pricing power or sales densities.

- Change of strategy: The very fact a strategy that worked for so long requires changing is rarely a good sign.

- Management changes: On the whole, executives have an excellent track record of getting out at the top. The incentive to reveal skeletons in the twilight of a management’s tenure is very low.

- Increasing capital intensity (for a given level of growth): It usually means the company is having to run harder in order to stand still. One of the easiest ways to maintain P/L growth is to increase capital investments. A new shiny store drives sales. A new factory improves output and lowers operating costs. The P/L hit comes later when the sales pick-up fades (as the store ages) and/or costs increase (as depreciation expense ramps up).

- Straight lines: All companies experience dips and bumps along the road at some point, the ride is rarely perfectly smooth. For the 15 years leading up to 2012 Tesco had the lowest volatility of earnings of any company in the FTSE 100 and significantly below supermarket peers Sainsbury and Morrison. If something seems to be too good to be true, it usually is.

- Quality of accounts: Monitor both audited (are the accounting assumptions changing?) and unaudited (are the adjusted figures diverging from the IFRS figures?) company accounts.

- Cash conversion: It is rarely a good sign if cash flow growth lags earnings growth.

- Consistency of the KPIs management discloses or is remunerated on: When all is going well there is usually no reason to change them.

- Deteriorating relationship with stakeholders: Companies under pressure can resort to squeezing their suppliers and employees as in the case of Tesco.

- Company communications with the financial markets: Beware of those who cut dissenting sell side analysts off results calls or refuse to roadshow with brokers who have a sell recommendation on the stock. There is a famous video13from 2016 of the CFO of a Chinese company throwing an analyst out of a results meeting because of his negative recommendation on the stock. The company’s earnings (and share price) subsequently collapsed.

- Corporate governance, in particular independence: PWC was Tesco’s auditor for 30 years, the fourth-longest auditor relationship in the FTSE 100. Look out for counter powers too. In the case of Tesco the Chairman of the Board had worked elbow to elbow with Sir Terry Leahy for decades making him far from independent.

- Do as they do, not as they say: Analysing director dealings is an imperfect science (managers can sell their shares for any number of reasons) but there are more than a few examples of directors selling ahead of a stall, including Tesco.

- Be conscious of culture when evaluating a change in strategy: Some cultures are adaptable, some are not. In the words of Peter Drucker “Culture eats Strategy for breakfast”.

HOW DOES COMGEST SCORE?

In 2008, the Harvard Business Review published a paper called “When Growth Stalls” in which the authors analysed some 500 growth companies over 50 years in order to assess the nature and propensity of stall points. They concluded that only 10% of the companies analysed managed to eschew a stall, defined as a sudden and unexpected slow-down of growth. Maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage is rare indeed.

Over Comgest’s history, we too have seen quite a few companies stall, including a number of portfolio holdings. In preparation for this White Paper, we decided to turn the spotlight on ourselves, and assess our own performance. We applied the same methodology as in the Harvard Business Review to stocks held in our European and Emerging Markets portfolios since 1996. The results make for interesting reading.

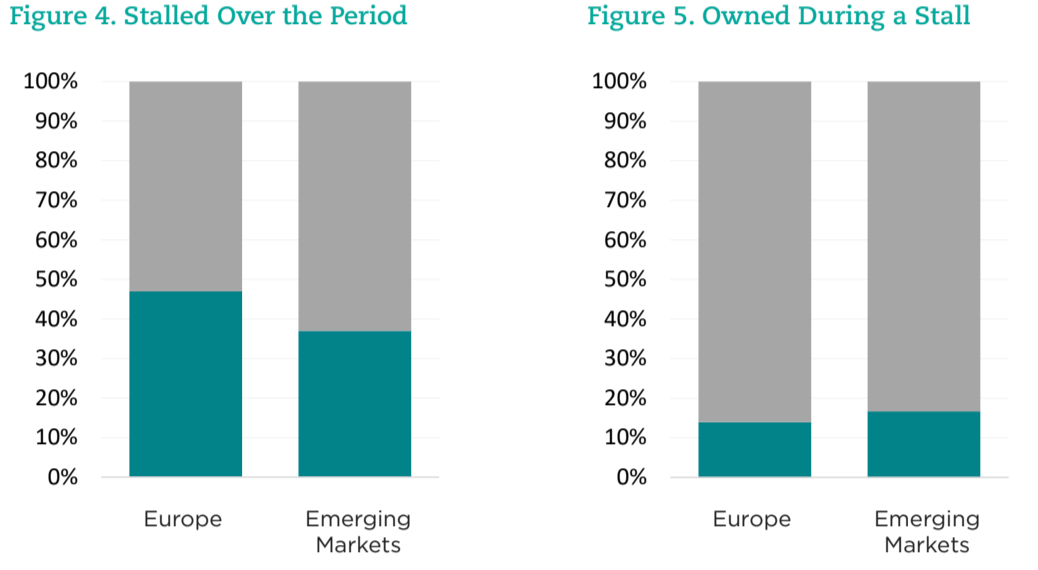

As per figure 4, of the 93 companies held since 1996 in Comgest’s European portfolio and for which we have data, 44 of them experienced a stall at some point (47%), whether owned at the time or not. The equivalent figures for the Emerging Markets portfolio was 47 out of 126 (37%). Stalls are indeed common.

Source: Johnston, Alastair. “Tesco – Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before”. Citigroup Global Markets, Citigroup Investment Research & Analysis. 13 Jan 2012.

Source: Johnston, Alastair. “Tesco – Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before”. Citigroup Global Markets, Citigroup Investment Research & Analysis. 13 Jan 2012.

The critical question, of course, is did we manage to avoid them? With regard to Europe, we managed to avoid owning 31 of the 44 stalls for part or all of it. In Emerging Markets, the figure was 26 out of 47 meaning that overall only a small portion of stocks in either strategy experienced a stall while being owned (figure 5). This suggests not only that we selected stocks that on the whole didn’t stall, but of those that did, we managed to avoid the majority of them. That being said there is still room for improvement and only by humbly learning the lessons of the past can we hope to continue to improve on this result.

CONCLUSION

In order to avoid a stall, the challenge is to remain objective and review portfolio holdings daily – as if they were new

As with any investment style, Quality Growth investing has its challenges. Selecting the rare sustainable growers is no easy task. Spotting the Tescos of tomorrow and exiting them on time is even harder and a skill that needs continuous fine-tuning. We must challenge ourselves to remain objective, to retest our thesis, to start each day and look at the portfolio as if we were buying each company for the first time. As long-term, high-conviction investors - we rightly have high barriers to entry when it comes to our portfolio. We must be aware of our “endowment effect risk” to ensure we do not unknowingly create equally high barriers to exit.

Update: On 6 December 2018, two of the former Tesco directors were acquitted of charges of fraud and false accounting after the judge dismissed their case due to lack of evidence.14On 23 January 2019, the final Tesco executive accused of fraud was also acquitted, leaving the SFO without a single conviction for the TESCO accounting scandal.15

REFERENCES

1 “Tesco Bosses Fiddled The Books To Save Their Jobs.” Court News UK (https://bit.ly/2Llj3BM). 29 Sept 2017; Butler, Sarah. “Former Tesco executives pressured others to falsify figures, court told.” The Guardian. 29 Sept 2017.

2 Update (May 2019): “Tesco directors aquitted in fraud trial,” BBC News (https://bbc.in/2Rz7M3v), 06 Dec 2018.

3 For an idea of scale: $5bn was close to the market capitalisation of UK-based Sainsbury at that time, but Sainsbury had $32bn of sales, $600m of profit and 820 much larger and mostly freehold stores.

4 Pouler, Sean. “Rip-off Britain: Food and fuel rises lead to highest inflation rate in West.” The Daily Mail. 3 Mar 2010.

5 Johnston and Wittet. “Tesco – 1Q10/11 Sales Preview”. Citigroup Global Markets, Citigroup Investment Research & Analysis. 25 May 2010.

6 IFRS Standards (https://www.ifrs.org); to be precise, it adjusted for: IAS 32, IAS 39, IAS 19, IAS 17, IFRS 3, IFRIC 13, IAS 36 and “restructuring costs.”

7 In a research report entitled “An Alternative P&L” analysts at Citigroup (the team for which this author worked) compared Tesco’s accounting policies with those of Morrisons’ in the UK and concluded that by applying more aggressive accounting policies Tesco was inflating its earnings by 20%. Source: Johnston and Wittet. “An Alternative P&L”. Citigroup Global Markets, Citigroup Investment Research & Analysis. 29 June 2010.

8 There were reports of Tesco making charitable donations to local authorities in order to secure planning permission. The Tescopoly Alliance, launched in June 2005, highlights and challenges the negative impacts of Tesco’s behaviour along its supply chains in the UK and internationally, on small businesses, on workers, on communities and the environment

9 His nickname derived in part from his uncompromising approach to employees. See “The man who built Tesco, ‘Slasher’ Jack Cohen.” BBC News (9 Sept 2013).

10 Neville, Simon. “Inside Tesco’s bonus-fuelled regime of fear and machismo.” The Independent (26 Sept 2014).

11 Butler, Sarah. “Tesco staff under pressure to hit financial targets, fraud trial hears.” The Guardian (5 Oct 2017).

12 Ahmed, Kamal. “Tesco, what went wrong?” BBC News (22 Oct 2014).

13 Reuters. “Macquarie Analyst Thrown Out of PAX Global Briefing After Heated Exchange.” Fortune (11 Aug 2016).

14 Update (May 2019): “Tesco directors aquitted in fraud trial,” BBC News (https://bbc.in/2Rz7M3v), 06 Dec 2018.

15 Wood, Zoe and Sarah Butler, “Former Tesco executive Carl Rogberg cleared of fraud”, The Guardian (https://bit.ly/2CrF6n2), 23 Jan 2019.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION - FOR PROFESSIONAL/QUALIFIED INVESTORS ONLY

Data as of 30 June 2018, unless stated otherwise. Product names, company names and logos mentioned herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. This document has been prepared for professional investors only and may only be used by these investors. This material is for information purposes only.

No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security/ investment. The companies discussed do not represent all past investments. It should not be assumed that any of the investments discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations or decisions made in the future will be profitable.

Past investment results are not indicative of future investment results. The value of all investments and the income derived therefrom can decrease as well as increase. This may be partly due to exchange rate fluctuations in investments that have an exposure to currencies other than the base currency of the fund.

Investing involves risk including possible loss of principal. Forward looking statements may not be realised. Product names, company names and logos mentioned herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.

The information and any opinions have been obtained from or are based on information from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. No liability is accepted by Comgest in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this document. The information in this document is not comprehensive and is presented for informational purposes only. All opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change without notice. Forward looking statements, data or forecasts may be not be realised.

Comgest does not provide tax or legal advice to its clients and all investors are strongly urged to consult their own tax or legal advisors concerning any potential investment. Before making any investment decision, investors are advised to check the investment horizon and category of the investment /fund in relation to any objectives or constraints they may have.

Investors shall undertake to respect the legal, regulatory and deontological measures relative to the fight against money laundering, as well as the texts that govern their application, and if modified investors shall ensure compliance.

The investment professionals listed in this document are employed either by Comgest S.A., Comgest Asset Management International Limited, Comgest Far East Limited, Comgest Asset Management Japan Ltd., Comgest US L.L.C. and Comgest Singapore Pte. Ltd.

Comgest S.A. is regulated by the Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF). Comgest Far East Limited is regulated by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission. Comgest Asset Management International Limited is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and is registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Comgest Asset Management Japan Ltd. is regulated by the Financial Service Agency of Japan (registered with Kanto Local Finance Bureau (No. Kinsho 1696)). Comgest US L.L.C is registered with the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission. Comgest Singapore Pte Ltd, is a Licensed Fund Management Company & Exempt Financial Advisor (for Institutional and Accredited Investors) regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

FOR HONG KONG ONLY: This advertisement has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong. FOR SINGAPORE ONLY: This advertisement has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

FOR AUSTRALIA ONLY : Comgest Far East Limited is regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission under Hong Kong laws, which differ from Australian laws. Comgest Far East Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence under the Australian Corporations Act in respect of the financial services that it provides. This material is directed at “wholesale clients” only and is not intended for, or to be relied upon by, “retail investors” (as defined in the Australian Corporations Act).

Comgest Singapore Pte. Ltd. is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore under Singaporean laws, which differ from Australian laws. Comgest Singapore Pte. Ltd. is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence under the Australian Corporations Act in respect of the financial services that it provides. This material is directed at “wholesale clients” only and is not intended for, or to be relied upon by, “retail investors” (as defined in the Australian Corporations Act).